Why Burberry should be bourgeois

How "edgy fashion" damaged Burberry, and what's next for the UK's only global luxury brand

What went wrong at Burberry?

Alfred Tong

“It's not a brand that I get asked to look at by my clients, even my high net worth ones,” says Anna Berkeley, personal stylist and author of Ask a stylist column in the Financial Times. “There is literally zero interest.”

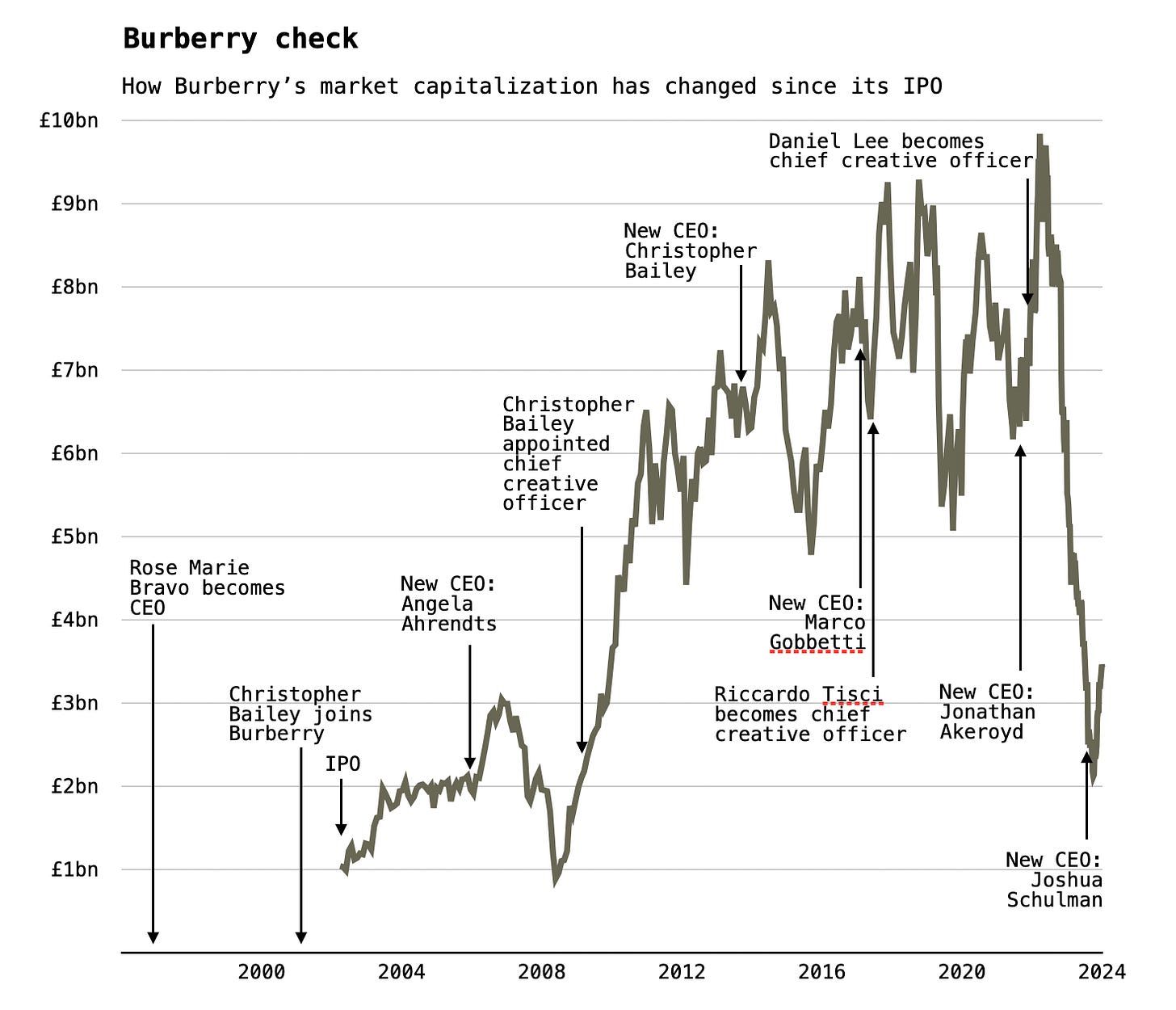

Something has gone badly wrong at Burberry, Britain’s largest, and only, global luxury brand. The value of the company is £3.4 billion, down from a peak of nearly £10 billion at the start of 2023. Revenue is down 22% in the six months to September 2024.

Before we dive into our analysis of what’s gone wrong at Burberry it's perhaps worth revisiting the copy on our about page.

“Fashion and luxury is not as scientific as other investments because it is 50 per cent art and magic – the untouchable – and 50 per cent business.”

In short, a €1.5 trillion global business often hinges upon little more than a certain “je ne sais quoi”

We find that in the luxury industry, there’s often plenty of analysis of the business bit with not enough about the “magic” bit, which can make or break multi-billion dollar publicly listed companies almost overnight. So that’s what we’re going to attempt to do with Burberry.

A core part of the investment case of Burberry is whether it can conjure up the success it had during the early 2000s. It’s not just a matter of hard data about supply chains, customer behaviour, e-commerce, manufacturing, macro-economic shifts in China, or industry-wide turmoil taking place in luxury overall. It’s also about the “intangibles,” the sense of style and creativity, that are hard to define but easy to detect, especially on the bottom line.

I interviewed three experts to try and help me understand what’s going on:

Peter Howarth, journalist and CEO of SHOW Media, former editor of Arena, Esquire UK, Man About Town, and style director of British GQ, who interviewed Burberry’s former creative directors Angela Ahrendts and Christopher Bailey in the brand’s heyday.

Anna Berkeley, the FT columnist mentioned in the introduction, who is a personal stylist and a former womenswear buyer. She spent seven years at Selfridges, when she was responsible for buying Burberry products for the department store.

Jonathan Towle, Thomas Pink’s director of marketing, who was previously at Paul Smith for 20 years, and who is familiar with the inner workings of the brand and the people there.

A bit of Burberry history

Burberry’s revival was initially masterminded by the Bronx-born Rose Marie Bravo, the former Saks Fifth Avenue CEO who took over in 1997. Before that, Burberry was essentially a licencing business built around the company’s famous check pattern. Bravo began the process of buying back licences to gain control of the company’s image and product, moving it upmarket in the process. She also launched its IPO and hired Christopher Bailey from Gucci.

Fellow American Angela Ahrendts took over as CEO in 2006 and carried on the work of streamlining manufacturing, marketing, branding, design, and retail operations so that almost everything focussed on the company’s iconic trench coat. In fact, Ahrendts bet the house on the trench.

“When I first met her, she was absolutely clear about her vision for the brand,” says Peter Howarth. “The first outfit out on a show is a trench coat. There's always a trench coat in an ad campaign. If there's a fragrance campaign, somebody is in a trench coat. And you know, the trench coat that comes out in the show doesn't have to be a classic trench coat, but it has to be a trench coat,” he says.

She also centralised all design and creative under the leadership of Bailey, who had a knack for bringing to life a romantic fantasy of modern Britishness that resonated internationally, if not at home. The result? The company’s value rose during her tenure from £2 billion to nearly £7 billion.

So what was the secret sauce? The sensibility and style that drove everything? Paradoxically, for a brand that trades in ideas of upper class Britishness, her homespun roots in Middle America (she grew up in Indiana) and mass market experience, combined with Bailey’s similarly modest Yorkshire background (his mum was a window dresser for Marks and Spencer), may have been fundamental. Crucially both were never interested in being “cool” or “trendy,” were close to their families, and (by fashion standards at least) considered unusual for being quite “nice.”

“In many ways, they pulled off an amazing sleight of hand,” says Peter Howarth, who interviewed Ahrendts during this period. “It was fashionable in the sense that it was on the catwalks and written about in the magazines, but actually, as a collection, it was never trying to be trendy. I think in some respects, it was very much a reflection of Christopher Bailey's own character.”

Even at its height, Bailey's “Prorsum” - the now discontinued high-end line and creative heartbeat of Burberry - was often criticised for being insufficiently “edgy” and too safe in the context of a London fashion scene known for its creativity and youthfulness. Howarth believes the essential classicism of the look was what made it work, especially overseas.

“It wasn’t cutting edge, because Bailey understood that this was a company that sold nice bourgeois clothes to a nice bourgeois clientele, often made up of tourists and slightly older people”

“You'd go to these shows and they'd reference David Hockney or the Bloomsbury set soundtracked to The Smiths,” says Howarth. “It was all very British and it was kind of art-schooly in a way, but it wasn’t cutting edge, because at his roots Bailey understood that this was a company that sold nice bourgeois clothes to a nice bourgeois clientele, often made up of tourists and people slightly older.”

A “bourgeois” sensibility, meaning to be somewhat conventional in outlook and aesthetics, is by no means “boring” says Howarth - nor small. There’s a thriving group of hugely successful bourgeois brands like Ralph Lauren, Giorgio Armani and Hermès. “Hermès doesn't have all the cool kids buying it,” says Howarth. “And yet, I haven't met a fashion designer who doesn't cite it as a brand they really admire.” Some brands like Chanel, Louis Vuitton and Gucci, while sometimes presenting as cutting edge fashion labels, derive a large part of their sales from icons of bourgeois taste, such as snaffle bit loafers, quilted handbags, bouclé wool jackets and monogrammed luggage.

“Armani even used the word ‘bourgeois’ to describe the ad-campaigns shot with his main collaborator, Aldo Fallai,” says Howarth. “He emerged in the aftermath of various political and economic crises in Italy and they wanted to portray decent, successful, middle class people in a hardworking society. A lot of the imagery involved chic professional men and women reading newspapers in cafés and piazzas in Milan.”

Bourgeois brands go in and out of fashion and take a long time to build, but their essential appeal rarely wanes and they offer a long-term hedge against the volatility of high fashion. They are led by ‘style’ and ‘quality’ and a romantic fantasy of national identity - think Richard Curtis not Mike Leigh - that plays well outside of their home markets. “Bourgeois is now a pejorative term,” says Howarth. “It’s so old-fashioned that people don’t even use it anymore. Everyone wants to be cool and trendy.”

The other great paradox was that Burberry’s home market was of relatively little importance to the company’s bottom line. Instead, it focused on selling a notion of Britishness that played well in its core markets of the US and China. The choice of Emma Watson (in a trench of course) as the face of the brand for the Winter 2009 campaign is a prime example. Unlike Kate Moss, Watson was not a particularly potent fashion symbol in the UK. Instead, she was world famous for her role in Harry Potter — a franchise that in many ways sold a similarly wholesome idea of Britishness. “She is perfect for us —and a very nice girl,” Ahrendts told the Wall Street Journal at the time. “It was genius,” says Howarth. “Because she’s not trendy. She’s a nice girl, she’s like Kate Middleton, who would be perfect for Burberry too.”

When it started to go wrong

Howarth believes it started to go wrong when the company pivoted towards an edgier idea of Britishness based around youth culture under subsequent creative director Riccardo Tisci, who was known for his streetwear inspired reinvention of Givenchy. Meanwhile, his replacement, Daniel Lee, was famous for his virtuosity in leather goods at Bottega Veneta. This heralded a move away from the trench into expensive handbags, which offer high margins, but are a category in which Burberry has no authority.